“We’ve never had it so good” is an oft repeated phrase when people talk about the amount of choices that are available to aficionados of whisky. While this may be true as the range of techniques and availability of different barrels have evolved, it’s worth thinking about the fact that there were more whisky distilleries in Scotland at the turn of the 20th century than there is currently. There was a whopping 159 in 1900 alone, with an all time low of 8 in 1918, though we must take into account the effects of World War 1 and conscription. Post WWI in 1921, the peak reached a maximum of 134, but was in decline until distillery numbers started to rise quite a while after the end of World War 2.

People who know a bit about whisky lament the closures of the 1980’s where many distilleries disappeared, even though production had been cut back and short time working was prevalent in many distilleries. While some have been revived, or are in the process of being brought back to life, many such as Convalmore, St Magdalene, Glenugie, Glen Albyn, Glen Mhor or Glenury Royal will never distill again. Despite many rumours and much wishful thinking of Dallas Dhu potentially being reactivated, I think the cost of rejuvenation will be prohibitive, even though all the equipment is still there, potentially ready to go. It may be good to look back on tradition, but things have moved on since the Victorian era. And looking towards modern times, few seem to realise that whisky always has had a precarious side to its business, with a raft of closures in the early 20th century, which was reinforced by economies being distorted by conflict and financial turmoil.

So, I’ll do what I tend to do best and look back into the past and tell the tale of a distillery that has been extinct for 110 years. This distillery never survived long enough to see the events of the First World War, closing in 1913, yet the story didn’t end there. Unless you know a little bit about local history of the area, many people wouldn’t even realise that there was ever a distillery in that area. I’ve been passing the site for years and never guessed, had it not been for a release that started the mystery unravelling.

A beginning

I’ve been a regular traveller on the road between Aberdeen and Inverness for years. One of my many geeky hobbies is to trace the routes that I travel on online Ordinance Survey maps. I love looking at the place names, or picturing them in my minds eye when I am away from home. One place I often saw was a farm named Jericho. I found it amusing, as it sat beside the Jordan burn. Obviously whoever named these may have had a religious lifestyle. It was only when the Lost Distillery Company released their range of whiskies which supposedly had been blended to be a close reproduction of the distilleries they represented did the penny drop. Originally, the range had 7 distilleries in the collection; Auchnagie (Highland), Dalaruan (Campbeltown), Gerston (Highland), Jericho (Highland), Lossit (Islay), Strathearn (Lowland) and Towiemore (Speyside). Unfortunately there has been a bit of a rebrand and the Auchnagie and Gerston bottlings have been dropped. What became rapidly apparent was that I’d not realised was how large Jericho had been and how it’s presence still resonates today, albeit slowly diminishing.

First issue was to get hold of a sample, and thankfully there was a miniature set of 6, in which I’d receive 6 of the 7 distilleries. All the pictures had Jericho in them, so duly ordered. When it turned up, the only missing one was Jericho. So I tried again and got another set without Jericho. I wasn’t wanting to go for third time lucky so bit the bullet and bought a full size bottle. Fortunately, a chance visit to a convenience store in my home village with a very good whisky selection had miniatures of Jericho in stock, negating my need to open the full size bottle. Interestingly enough, two of the other distilleries which are in the collection I also happen to pass nearby to on occasion, so will be looking to review them at a later date.

A distillery is born

There’s precious little left nowadays of Jericho distillery, just some ruins which would give you no idea what they once were. It was a more religious than normal farmer called William Smith who started distilling at Nether Jericho farm around 1822. We assume this was the date, as whisky from the distillery which was later sold in 2 Gallon ceramic ‘pigs’ (akin to a 10 litre barrel), had the date 1822 embellished on them, although is for Benachie whisky, the name the Jericho distillery took on later. In 1983, two of these pigs were known to survive, but sadly without the original contents. As mentioned previously, the water source was the Jordan Burn, in which its flow and quality of water was instrumental in making a successful distillery, being used for all the needs of the distillery. Old maps show that the burn also fed a small reservoir which was added later on, perhaps to give a head of water pressure to drive machinery at the distillery, as well as supplying the liquid to make whisky.

It wasn’t the only farm distillery in the area to open in that era, there was also one on the other side of the Glens of Foudland, just to the north of Huntly on the banks of the River Bogie called Pirriesmill, which opened in 1824, but sadly didn’t last as long as Jericho, presumably being mothballed prior to being reopened in 1832. It ran for at least another 35 years but by maps of 1870 was listed as disused. The archive version of scotchwhisky.com lists the distillery as Speyside, which is totally incorrect as Speyside as a region did not exist at that point in time, and Huntly is firmly in Aberdeenshire, and not part of Moray or Strathspey & Badenoch regions which constitute modern day Speyside. There is one building that still exists and can be seen when passing on the train between Huntly and Keith. Judging by old maps, this distillery seems to have been a fair size too. The ordinance survey map made in 1871 had noted the “Old Distillery” at Pirriesmill, but still shows the buildings. I can’t display the map here due to copyright but here’s a link to it Pirriesmill Distillery

So, back to Jericho. A licence was obtained for the distillery in 1824 after the 1823 Excise act had passed, though it is not clear whether or not distilling had already started. Had William Smith been an illicit distiller is anybodies guess, but it is safe to say that he would have been in good company with his fellow countrymen. In 1822 the Illicit Distillation Act had been passed which not only continued making the unlicensed distillation illegal, but also the purchase and consumption of unlicensed spirit was also criminalised. Not that this deterred many people as the area around Jericho is very rural, and while not remote by modern standards, would have been bleak back in 1822. A good account of the battle between gauger and distiller is told in the book “Illicit Scotch” by S.W Sillett, in which he tells stories of secret whisky making in the north and northeast of Scotland. Remember, the railway wouldn’t make it to this part of Scotland until 1854 when the railway between Aberdeen and Keith was completed, with the nearest railway station being in Insch, some 5 miles distant. One can imagine the distillery either selling its produce locally or using horse and cart to take casks to Aberdeen for onward sale. Once the eventual opening of the railway occurred, there was a steady flow of traffic to the goods yard at Insch station. According to an article by Michael G Kidd in the book ‘Bennachie Again”, carts used to be nose to tail in the Glens Of Foudland, which is the route of the modern Aberdeen to Inverness road. I’ll be referring to this book often in this piece.

A year after the release of the Illicit Distillation Act, the more widely known Excise Act was passed on the 18th July 1823, which lowered the Tax burden to the distillers, making legal distilling a lot more desirable. It is amusing that one of the main proponents of this act was the 4th Duke of Gordon, a man who owned a lot of the land that was being used for illicit distillation! Perhaps being the God-fearing man that Wiliam Smith reportedly was meant that he decided to licence his distillery, but it is somewhat ironic that it was taxes that helped seal the fate of the Jericho distillery some 89 years later.

From what I’ve been able to find out, Jericho distillery under Smith was pretty primitive, with a small wooden mash tun that was raked manually, which led to a lumpy mash and poor sugar extraction. The distillery most often used Bere barley, which while this was a popular grain for whisky making, the grains aren’t all the same size, which makes it more difficult to malt and mash. It was also more prone to rot, which would have been problematic given the quality of storage compared to a modern distillery nowadays. The kiln was powered by peat, which was a readily available fuel source. The distillery had 6 washbacks of 880 gallons capacity each, the wash still was capable of holding 244 gallons and the spirit still only 67.5 gallons capacity, which indicates that the output would be very low.

The yeast used initially for fermentation is likely to be home grown cultures and wild yeast. Home grown yeast tended to be made from potatoes and sugar, which was prone to making off-notes and frequently full of contaminants. Wild Yeast is airborne, unpredictable and not tolerant of low ambient temperatures. Yeast activity is also temperature driven, meaning that the times of each fermentation would be inconsistent, and therefore so would the strength and quality of the wash be variable. Given these facts, it’s unlikely that Jericho managed to consistently mash and get a good yield of sugars, and also possible that not every fermentation was of good quality either.

By 1864, William Smith had decided to retire, with the tenancy of Nether Jericho Farm being taken over by his stepson and assistant, John Maitland at the age of 25. Maitland set about modernising the distillery slowly but surely. By the late 1860’s the mash tun had been replaced by an iron tun, some 12 feet in diameter and 4 feet deep, and was fitted with rakes which improved the quality of the mash.

Referring back to the book ‘Bennachie Again’, it is revealed that a man called William Milne came to work at Nether Jericho farm and distillery as a ‘greive’ which is a Scottish name for a farm supervisor. There were 6 horses to do the work of the farm and the distillery but at this stage we do not have any firm idea how many people worked at the distillery. Workers at the distillery may also have had to undertake farm work also – just like Daftmill! It is also not known how long William Milne was at Nether Jericho, but before he moved to Rothes around 1900, he had been borne a son called Thomas around 1892, and we’ll meet Thomas Milne later in this story.

During the 1870’s the use of sherry casks became popular. Sherry used to be shipped to the UK in European Oak transit casks, a practice that was stopped by the Spanish Government in 1980, who insisted sherry had to exported in bottles. Jericho did use sherry casks in its maturation, and this is reflected in the recreation made by the Lost Distillery Company. Sadly, John Maitland died at the age of 40, leaving behind a wife and five children. Jericho then fell silent for a few years.

A New Beginning and a New Name

In 1883 Messers. William Callander and John Graham purchased the farm and distillery lease, and set about making more improvements. The distillery was now going to be known as the Benachie Distillery. The name comes from the locally well-known hill called Bennachie, which is just to the south of Nether Jericho farm. It is a series of tops with the most easterly one being the most recognisable and is known as the Mither Tap. The hill can be seen from quite a large swathe of Aberdeenshire, and is quite prominent as it looks over the Garioch, where a lot of the barley for local whisky production would have been grown. It is interesting to note that they did not use the correct spelling of the hill which is locally pronounced Benn-a-hee. For those of you who don’t already know, Garioch is pronounced gear-ee, with the G being a hard G, similar to that used in ‘Ground’ and the word would rhyme with dreary.

Why this name change was seen as necessary I do not know, but what is known that by 1884 the distillery underwent a transformation and seems have partially rebuilt. The distillery was built in the style that is common to agricultural buildings and many distilleries of the region at that time using squared granite rubble stone. I am guessing that the name change was to perhaps identify that the distillery had been upgraded and therefore may not be the same. The new stills were still small and squat, but had taller necks, so would have produced a lighter spirit than Jericho, although the whisky was still sold as Jericho for a few years afterwards. Also, by this time, things had moved on, with the railway now available at Insch, therefore whisky from Jericho would now be able to be distributed to a larger area, though the distillery still relied on horse and cart to get their produce to Insch railway station. It was intended that the improvements to Jericho were to be finished by October 1884.

Where we do get a good overview about the Benachie distillery is from the well known book written by Alfred Barnard in his book The Whisky Distilleries of The United Kingdom, published in 1887. If you read the book, you can see that Barnard seems to have gone around Scotland in a clockwise direction, having visited Glendronach distillery near Huntly before travelling to Nether Jericho. The opening lines make me chuckle – “It would puzzle you to find a more desolate drive than that from Glendronach to Benachie distillery. The mountain road is one of the bleakest and most lonely that we have traversed. ” I have to laugh as I wonder what Barnard would make of the modern A96 road through the Glens of Foudland – a road even in the 21st century still can get closed by drifting snow. I guess all that seems to have changed is that we now have tarmacadam carriageway with crawler lanes. Perhaps Barnard suffered the lack of a direct rail link as much as Jericho did.

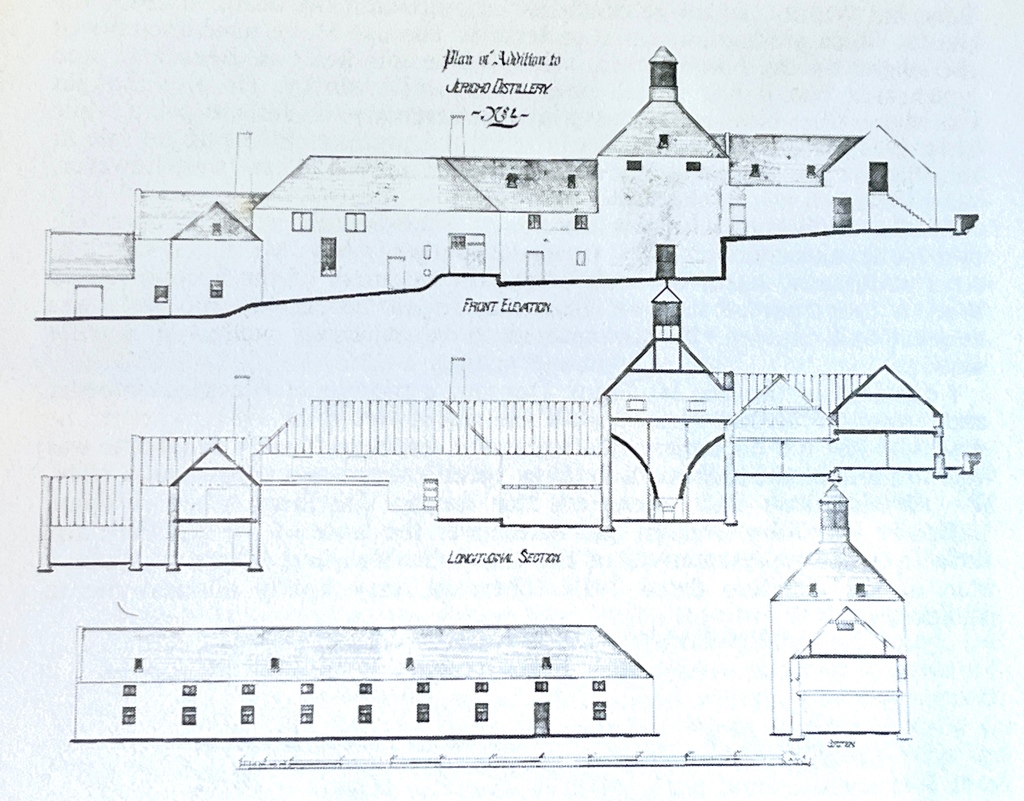

Barnard tells us that the distillery had 2 malt barns that had two floors of 140ft length and a width of 25 feet, with the top floor using the top for grain storage and the bottom for malting. Next was the malting kiln, which was approximately 24 ft square, and we can see from the architect plans it was fitted with a traditional Doig ventilator. Local peat was used as fuel for the kilning process, but would be a lot more subtle than that of the Western Highlands, and more inline with the peat usage of the era in Speyside. Further down the hill is the milling room which is next to the mash tun. This is recorded as being 4 ft deep and 12 ft wide with revolving stirring gear, powered by water power, (as previously fitted by John Maitland). The wort is then cooled and transferred into the adjacent tun room that held 4 washbacks of 3,000 gallons capacity each, or around 13,600 litres. The still house is at the foot of the hill, containing the 2 stills and their receivers, wash, low wines and the feints chargers. The wash still had a capacity of 1400 gallons and the spirit still had a capacity of 706 gallons. No mention is made of the condensers, but I am assuming that worm tubs were used, as a black and white photo of the site in 1910 shows what looks like a black cylinder close to the rear of the building. The spirit vat had a capacity of 1100 gallons, which if this is the capacity of undiluted spirit that it could hold, and if average spirit strength before dilution was 70% abv and cask fill strength was 63.5% would be enough for 22 Hogshead casks. I think this is generous as similar sized distilleries with one spirit still run a day only manage about 14 Hogsheads a week with a clearic strength of 72% and cask fill at 63.5%. It’s my guess that perhaps spirit would be casked every 2 weeks at Jericho. Assuming a 40 week distilling season, in theory if the vat was emptied every fortnight, then the distillery would then be able to produce 440 casks a year. I’m assuming things based on modern distillery practices, and without knowing what Jericho filling strengths were, how regularly they had mashings, how long the fermentation was or if the distillery was only ran when farm work didn’t intervene. However, I think my calculations tie in with the reputed storage facilities as I’ve seen it written that the distillery only had room for around 400 casks.

This leads to the issue of immature spirit. None of the casks under the previous example could have been held for more than a year, and at the start of production at Nether Jericho there is a good chance the spirit wasn’t cask matured at all. The Immature Spirit act wasn’t to follow until 1915, so the produce of the Benachie distillery may have been to coin a word – rough. From what has been stated by The Lost Distillery Co on their Jericho release was that Sherry Casks were used for the maturation of whisky at the Benachie Distillery. Perhaps a 1st fill European Oak cask made the spirit palatable after a year of maturation? Maybe the smoothness of Jericho was relative, and it just wasn’t as rough as other products!

The improvements that had been made to the distillery at Nether Jericho farm were a success, and advances in distilling practices, most notably the development of dry yeast by Dr Andrew Squires and Distillers Company Ltd in 1881, which would then give a consistent wash. With an ambition of producing up to 50,000 gallons, which in todays terms would put it in a rank similar to Lindores distillery at 2023 levels, and below that of Edradour, Holyrood and the RAER spirits distillery at Jackton in Glasgow. (Source – Malt Whisky Yearbook). From the anecdotes that I have read in various sources, the whisky was relatively popular, with the advertising slogan “There’s Nae Sair Heids in Benachie” on the label, which may imply that the whisky was a mild malt.

Benachie could be bought as a bottled whisky, and could also be bought in the ceramic ‘pigs’ as mentioned earlier, similar to a small cask of 2 gallons volume. Callander and Graham had a shop on the High Street of Insch where the whisky could be bought, and a receipt illustration in the book ‘Bennachie Again’ shows a 2 gallon pig sold for £1.15s.0d, which is £1.75 in metric. In today’s money, this would be worth £253.22, which to me is an absolute bargain for just over 9 litres of whisky, when nowadays many bottles cost more than that and aren’t even a full litre.

Clouds on the Horizon

Unfortunately, the good times weren’t going to last. The remoteness that had once made Nether Jericho an attractive place to illicitly distill was going to become a noose around its neck. The whisky wasn’t really distributed much outside the North East of Scotland. It wasn’t used in blends as far as we know as mentioned before. The disruption caused by the Pattison crash caused a lot of uncertainty in the industry, especially financially. Larger distilleries than Jericho had been built in the last few years of the 19th century only to close and disappear completely after less than 20 years production – the Speyside Distillery in Kingussie being a notable case. Plus, the overall quality of Scotch whisky as a whole was improving and more and more was being produced for blending by the newer distilleries that hadn’t started as an add-on to a farm. The Pattison crash also created a sudden oversupply in the industry, caused by whisky produced for blending that was no longer needed, rapidly having a knock on effect in sales of Benachie, as prices of other whiskies were likely to be dropping due to the mass production and a sudden loss of blending demand. With spirits being a lot cheaper, and the social problems it created, it was only a matter of time before Government waded in.

By 1909, The Chancellor of the Exchequer, David Lloyd George changed the taxes applicable to the whisky industry yet again, increasing by a third. Lloyd George’s ‘People’s Budget’ of April 1909 was to try and lift more of the population out of the poverty and squalor that many people lived in. However, it wasn’t just whisky that was affected – there was many areas of the economy had their tax regime change to start paying people a pension. An increase of price would also help reduce drunkenness. Profitability was falling too, and in the Pattison crash aftermath there was also an increase of consolidation under companies like Distillers Company Limited and Scottish Malt Distillers Ltd, both of whom would eventually fall under the Diageo umbrella many decades later. With more whisky that could be made cheaper by mass production, the profit margins of the small operators had to fall in an effort to be competitive. Small farm based distilleries had less access to the wider market and less money than the big companies to market their products effectively, life was hard for these small independent distilleries. And the enterprise at Nether Jericho didn’t have its challenges to seek.

Benachie distillery, being remote from the railway unlike its competitors at Glen Garioch and Ardmore, couldn’t easily take advantage of using coal as a fuel source, leaving the distillery shackled to using peat only. By 1913 William Callander retired, but with increasing economic pressures, lack of modern transport and being reliant on the local market would have led his son and heir William Callander Junior to feel that it was no longer viable to continue to produce Benachie whisky even despite having a relatively modern plant. The decision was made to continue farming only and the Benachie distillery finally fell silent. The first world war started little over a year later and that is likely to have put paid to any chance of the distillery reopening in the immediate future.

The previously mentioned Thomas Milne of Rothes became friendly with the publican of the Victoria Bar in the village, a Andrew McKenzie Grant, and he persuaded the bar to stock Benachie whisky, which the barkeep presumably enjoyed up to his death in 1913, the same year the distillery closed. Thomas must have thought there was a big stock of Benachie in the warehouse at Jericho, as it was still on sale in the Victoria bar when he went to war in 1915. There was doubtless none left when he came back.

The Chancellor, Lloyd George, was a teetotaller and would have no problem in targeting the spirits industry once again to raise finance. One of his other acts to apply more pressure to distillers was the formation of the Immature Spirits act of 1915, which was initially meant to try to stop workers drinking as much and make industry more productive. At one moment time the British Army was firing enough shells in one day that took 17 days to manufacture, which was clearly unsustainable.

Drink is doing more damage in this war than all the German Submarines put together.

David Lloyd George, Bangor, 27th February 1915

So, the Immature Spirits act came into being, and far from being the downfall of the whisky industry, it actually saved it. For the first time, whisky had to be matured in oak casks and matured for a minimum of 3 years. It is worth pointing out that many reputable whisky producers were already doing this, and the act initially would have got rid of the less reputable brands. From 163 prewar British distilleries to 20 post war, the bill may have had its desired effect initially, but this was back up to a total of 164 by 1920.

The bill that saved the whisky industry came too late for Jericho, but one must wonder how it would have been affected – after all with it now being prevented from selling immature spirit for consumption and only having storage for around a years production without additional warehousing being built at the very least, mean that combined with the issues of limited market and logistical issues, the distillery was always likely to be a casualty.

But there was somebody else that wanted to resurrect the distillery. Perhaps the increase of motorised transport available in the aftermath of the World War made operations more practical and economical. In 1920, there was a Memorandum of Agreement by the Benachie Distillery Syndicate, represented by Lawrence Chalmers, to purchase from William Callander, Farmer, Jericho, County of Aberdeenshire, by missives dated March and April 1919, the rights, interests and claims acquired by him. Under a Memorandum of the Association, the Syndicate was to acquire and hold, manage and develop, improve or otherwise turn to account the buildings with the farm of Jericho, including the buildings adjacent, formerly occupied as a distillery. But there was a major sticking point – William Callander Jr. did not sell the licence for the distillery with it. There was a legal battle for this in the Court of Session, but the court found in favour of William Callander. Without this licence, distillation could not restart, and it would be impossible to distill illicitly. This company continued until it was formally dissolved on the 1st of July 1960, with sadly no progress being made to restart the distillery.

Every account of Jericho / Benachie whisky ends with a story about how the locals used to enjoy dances and parties in the old barns at Nether Jericho. The author of Illicit Scotch, Steve Sillett told of the ancedote by his late father-in-law how at a wedding in Insch just prior to the outbreak of the Second World War, a long hoarded cask of Benachie was emptied and enjoyed. This was likely to be the last cask, and was reported to be extremely mellow if not a bit woody.

And that was the end, or was it?

By the late 70’s, there were still some remains of the distillery, where Michael Kidd had visited Nether Jericho. The Kiln had become dilapidated and roofless, but the rest of the line of buildings were still intact and gave an indication of what had been their purpose in the past. I myself visited in January 2023 with the permission of the landowner who showed me around the remains, of which there is not a lot left. Only one building hints to its former purpose as a distillery bonded store with barred windows. I am most grateful to the landowner for this opportunity, as I know famers do not like strangers wondering around their land taking photographs. Crime is something they don’t want to have in remote rural areas.

The present owner said that he had been at the farm for 30 years and knew a little bit about the distillery, but in his time there wasn’t a lot of the original buildings left. The line of buildings from the Kiln down to the slope are now all in ruins, with little to tell what was what building. Only a portion of the building that was used as a bonded warehouse remains, as do the walls of what might have been a malt barn. This used to have a semi circular tin roof that finally succumbed to a weight of snow in around 2010-2012. Turns out Glenfiddich weren’t alone with their storage collapsing! This barn (unusually) has the Jordan burn flow under it, and I am wondering if there was some sort of mechanism in this barn for turning machinery like the mash tun and mill, but I guess we’ll never find out. That is now lost, like the whisky to history.

Gone, but not forgotten

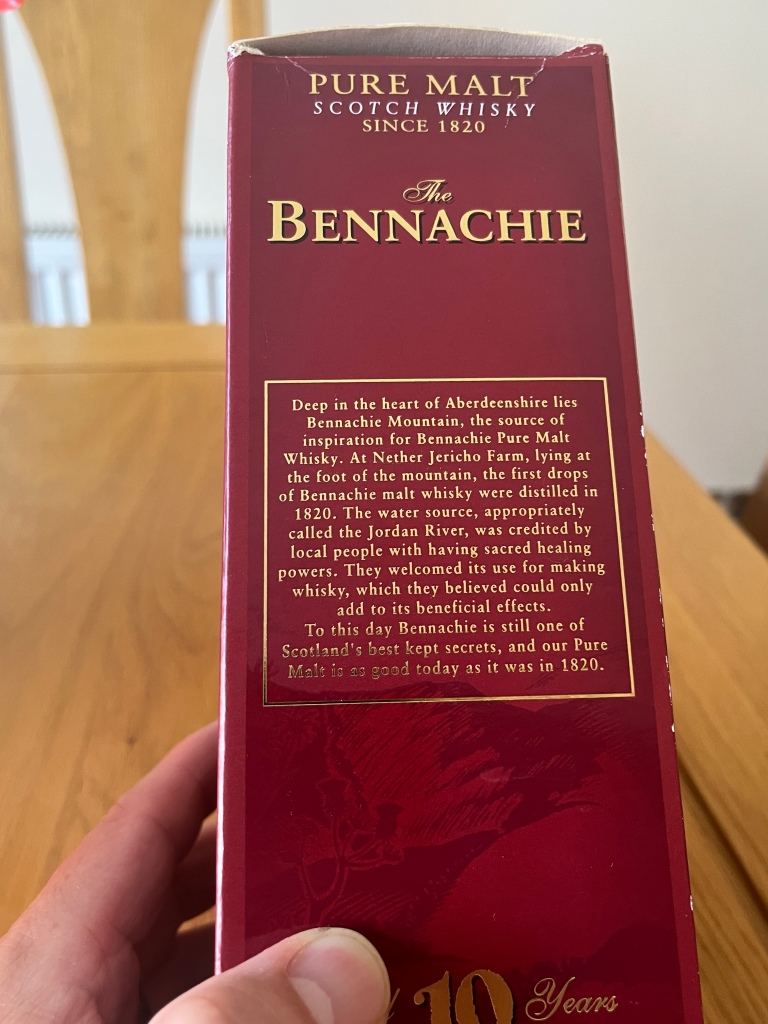

As I said at the start of this article, I never once realised there was a distillery at Jericho. I assumed the road sign on the A96 just referred to a farm owned by a religious person. It’s not that uncommon to do, as there is an suburb of Edinburgh known as Joppa, named after the port of the same name in the 18th century that is known now as Jaffa in Israel. I’ve seen the Bennachie whisky miniatures turn up at auction which I had a couple of, as they have come in a batch of miniatures that I have purchased for one specific miniature. The vatted malt as far as I am able to deduce was produced by a businessman called Euan Shand, who started the Bennachie Scotch Whisky Co in 1990 with an interest in blended malts. Euan comes from a background of whisky (his dad was the manager of Glendronach) and he’s now the chairman of Duncan Taylor Scotch Whisky Ltd, which I am sure many know. To date, I’ve seen the Bennachie vatted malt as a 10, 17 and 21 year old, and I think I’ve also seen bottles at 8 and 12 years old with different branding. Usually at 40 or 43% abv. I don’t think these are ever supposed to be an approximation of the original Jericho / Benachie Distillery whisky.

It wasn’t until I saw the Lost Distillery Company range of blended malts that were supposed to represent the type of whiskies made by 7 long gone distilleries that I managed to connect the sign for Jericho farm and the whisky together. The Lost Distillery Company have researched the distilleries that are long gone, and have made a vatted malt that will replicate the style of the distillery, although they never say that it will replicate the whisky exactly. So what better to do now than perhaps try some. And for good measure, lets try one of the Bennachie Vatted Malts.

Jericho – Lost Distillery Company

Region – Blend Age – NAS Strength – 43% Colour – Mahogany (1.6) Cask Type – Not known Colouring – Not Stated, but most likely Chill Filtered – Not Stated, but most likely Nose – Figs, raisins, muscovado sugar, orange peel, ginger, walnuts, cherry. Palate – Thin mouthfeel, ginger, dried fruits, nutty, peaches, redcurrant Finish – quite spicy when swallowed but the that soon dissipates. Chocolate gingers, pepper, slight creaminess. Short finish.

Bennachie Vatted Malt

Region – Blend Age -NAS Strength – 43% Colour – Jonquiripe Corn (0.4) Cask Type – Not known Colouring – Not Stated Chill Filtered – Not Stated Nose – while letting it sit beside me for 20 mins, I could smell green apples, malt, tinned peaches wafting over. Sticking my nose into the glass, the unfortunate smell of old bottle effect (musty cardboard) was present but not too bad. Biscuity, custard creams, fruit cake. Palate – oily and sweet. Alcohol is a bit harsh initially. Honey and digestive biscuits, citrus peel, hint of clove. Oak spices, malt. Adding water I found to introduce a bitter, acidic taste to the citrus notes Finish – medium short finish. Oak spices, citrus, honey. Water increases the oak notes and dampened the old bottle effect.

Tasting Conclusions

Both whiskies were pleasant enough. Jericho tasted a lot sharper and had a thinner mouthfeel than I was expecting, but this may differ in the other strengths of the Archivist or Vintage variants, which are at 46% and I am assuming use older whiskies. However, it wasn’t nearly as rough as I thought it would be, and I am glad that I have a full size bottle of this whisky, as it may need time to breathe in the bottle. The Bennachie vatted malt was the more pleasant of the two, and I’d go as far to say that I’m happy that I obtained a full size drinking bottle; albeit an earlier release.

Have We Never Had It So Good?

I started this piece by asking if we ever had it so good? I believe it is all relative, but I’d say yes and no. However the tale of Jericho and other lost distilleries repeat a tale that I believe still has a message for us today. I fell down many wormholes doing research. I wanted to find out how unique the tale of Jericho may have been. In 1900, there were 159 operating distilleries in Scotland, but by 1913, this had dropped to 127. This picked up again in the couple of years after World War One, but by 1933 it had fallen to 15. When we look at history, we can see that in this period there has been Prohibition in the US, War in Europe and the Great Depression which affected economies world wide all played their part. Perhaps by this time, the small farm style distilleries had become uneconomical and closed. Up to the late 1970’s the number of Scottish distilleries didn’t exceed 123.

We need a bit of context, in that people didn’t have the same ratio of disposable income that many of us enjoy. Businesses didn’t have so many prospective customers, and tax rises on luxury goods were more likely to affect what consumers would buy. And I think with the coming 10% tax hike announced in the UK spring 2023 budget, this will perhaps start influencing consumer spending as the UK struggles with inflation. Certainly the secondary bottle market has already started to see a correction. Spirits duty has been held at £28.74 since 2017. When we look back at the last big industry crash, in 1983 the increase of duty was only around 5%. I dread to think what difference a duty increase of double that amount will have on the industry and consumers.

The other thing that I noticed was the rate of taxation has increased and decreased over the years. According to a research website from Edinburgh University (See here), the tax on a single litre of pure alcohol was 21.2p in 1900. I am assuming that this takes in to consideration of imperial currency conversion and the fact that imperial measurements were used then. If we allow for inflation and use a historical inflation caluculator and assume I have done my sums right, that’s equivalent to £31.21 in today’s money. Quite a bit higher than the £28.74 per lpa shown by the gov.uk site at the time of typing, although this rises to £31.64 in August 2023.

And we look upon a background of 70 extra malt distilleries that have been built or are planned to be built between 2000 and 2030, we have to wonder who is going to be buying this whisky – as was the theme of the Aquavitae vPub on 20th April 2023 – link here to YouTube. With increasing taxation and the threat of war in Europe and China rattling it’s sabre at Taiwan, as well as global financial instability, one has to wonder how many distilleries may go the way of Jericho, when or if it becomes uneconomic to do so?

The counterbalance to the doom and gloom is that China has the equivalent of the population of the UK that reaches the legal age for drinking every year. That is a market waiting to be tapped. And similar would probably be India which has just overtaken China as the most populous nation and already has an indigenous whisky industry, albeit Scotch is still popular there. While population boosts are not new, Scottish whisky hasn’t been exported to the levels we are seeing now, however are we leaving our selves wide open should there be a change in drinking fashions and habits? There’s a lot of distilleries going flat out to produce, yet most don’t have a crystal ball to predict what will happen in 10 years time. If they do know, can they give me 6 numbers between 1 and 59 each Saturday night?

The whisky industry is cyclic, so in my opinion it’s foolish to assume there will be constant growth. Perhaps more realistically there will be ebbs and flows, but a steady overall upwards trajectory. But all it takes are external factors outside the industry control or a change in drinking fashion and we could easily be facing a whisky loch again. As I continue my theme this year and into next of silent distilleries, we can learn a lot from the whisky history that has gone before us.

Before I go, I would like to thank the people who have made this article possible. Firstly I would like to thank the owner of Nether Jericho who allowed me to take photographs of the surviving buildings. My second thanks it to Neil Wilson of NWP who allowed me to use the black and white photo of Jericho Distillery from the book Scotch Missed by Brian Townsend. Lastly, I would like to thank Ann Baillie, the Vice Chair of the Baillies Of Bennachie, who allowed me to use the layout from their book ‘Bennachie Again’, published in 1983. The Baillies of Bennachie are a charity that look after the pathways around Bennachie, and are heavily involved in the research and preservation of the historical communities that have existed on the hill. If you know about Bennachie and are interested, why not join the Baillies for only £10 a year (www.bailiesofbennachie.co.uk)

Yours In Spirits

Scotty

Photo Credits / Bibliography

All Photos – Authors Own – except

Nether Jericho / Benachie distillery – copyright Neil Wilson Publishing

Benachie Distillery layout – copyright Baillies of Bennachie / Frank Duncan / Michael G Kidd

Books and other references

Scotch Missed – Brian Townsend (NWP 1993)

Nae Sair Heids In Bennachie – Michael G Kidd ‘Bennachie Again'(Baillies Of Bennachie 1983)

Illicit Scotch – S.W SIllett – Impulse Books 1965

Number of Scots Operating Distilleries 1900-1979 – “Scotch Whisky Industry Record”, H. Charles Gray (www.dcs.ed.ac.uk)

Statistical Tables: Duty (www.dcs.ed.ac.uk)

All content subject to copyright and must not be reproduced without permission

You have upped your game Scotty, a helluva lot of work and research has gone into that piece of work.

A great and educational read as always…..well done and thanks.

Cheers fir noo

Steve Gray

LikeLike